The other day I went back to college. As a student. For 90 minutes. It was the quintessential autumn day. The kind where the leaves have just begun to turn color, some gently unhinging from their branches and wavering in the air before they hit the dirt below. Or in my case, before they hit the bricks that make up Locust Walk, the pedestrian pathway that cuts through the heart of Penn’s campus.

On the invitation of my daughter, now a sophomore at my alma mater, I arrived on campus—not just as a courier schlepping a winter coat, some homemade chicken soup and several necessities from Trader Joe’s, but primarily to attend a lecture in Emily’s class, Intro to Positive Psychology.

With a tendency to cut my timing close, I purposely gave myself an extra hour before meeting Emily so I could wallow in the beauty of the day, and the memories of my own walks down Locust Walk—nearly 30 years ago. I texted Emily to let her know where I was sitting–on the grass to the left of the iconic Button sculpture that sits in front of the main library–steps away from the hovering statue of Ben Franklin. I literally could not wipe the smile off my face.

I spotted her immediately as she walked up the path in my direction, dodging a few fellow students, most of whom had eyes glued to their phones. She pulled hers out too, discreetly placing it in picture-taking position as she approached. I knew she’d likely make fun of me, firing Snapchats to her friends and siblings. But I didn’t care. I was back at college.

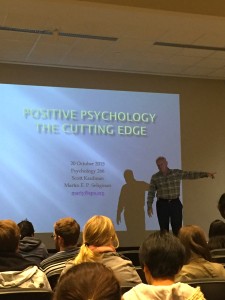

Emily had invited me to attend this particular lecture because the guest speaker was Dr. Martin Seligman, a renowned and longtime professor at Penn and known as the founder of Positive Psychology. Having recently become certified as a Positive Psychology practitioner and life coach following a year of study and training through the Wholebeing Institute, I jumped at the chance to accompany my daughter to class.

Together we walked to Meyerson Hall, which sits at the lower end of College Green, the central grassy quad on this urban campus. The nostalgia poured over me as I thought about the times I walked into the same lecture hall as a student—three decades earlier—for a

marketing class, as well as one on the Arab-Israeli conflict. I followed Emily down the side aisle and we took our seats, each with a wooden desk that turns and then flips up when you want to use it. Many students broke out their laptops; Emily used a notebook and gave me some paper to write on. I couldn’t wait to listen, learn, and take notes.

Dr. Seligman started his lecture by asking students the following: “In two words or fewer, what do you want most in life?” The students blurted out their answers: love, meaning, happiness, fulfillment. “Good,” he said. “Now tell me in two words or fewer, what are you learning in school?” Again, the students responded out loud: knowledge, how to get a job, discipline, bullshit!

Seligman went on to tell the group of about 80 students to notice the lack of overlap. “You’re being robbed because both can be taught in the classroom,” he said. “It’s possible to get more than a good job—you can also have fulfillment.”

For the next 90 minutes, Seligman discussed the five pillars of well-being, known by the mnemonic, PERMA, which stands for Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and Accomplishments. Dressed in a flannel shirt and navy slacks, he crisscrossed the stage, using slides and images to highlight his points, and word clouds to exhibit the latest study drawing on 50,000 words and phrases found on Facebook and Twitter. Occasionally stepping down from the stage to answer a question—he mentioned several times that he’s hard of hearing—he was direct, engaging and an obvious master of the topic.

I listened so intently that I felt the new wrinkles forming on my forehead. My laser focus was on his stories and research, and I jotted it all down on the loose-leaf paper Emily fed me. Was I this inspired 30 years ago? Did I ever feel disappointed that a lecture was about to end? Somehow I don’t think so. But from where I sat in Meyerson Hall, next to my 19-year-old daughter, I would’ve been happy to sit for a few more hours.

Seligman told the class that Freud and Schopenhauer had it wrong—their approach had been to look at how not to suffer, and how that was the mark of a good life.

Seligman followed suit, spending his first 30 years at Penn focusing on misery. But his work for the last 20 years has shifted to the study of well-being and the ways in which people can increase their life satisfaction.

After the lecture, I told Emily I wanted to meet Dr. Seligman. “I’ll wait for you outside,” she said without hesitiation. But minutes later, she joined me on the line to meet him (though we let all of the students go ahead of us). We said a quick hello and thanked him, and I told him that I was a Penn alum, studied Positive Psychology recently and had come from New York to hear his lecture. He didn’t seem to care.

But for that afternoon, I felt fulfilled and grateful and happy. The time with my daughter, in an environment where I could listen and learn, on a day when the sun was shining, in a place to which I feel connected—the pillars of PERMA were working for me. It was just great to be back at college.